De Londres à Osaka - Une histoire des expositions universelles qui ont dessiné notre avenir

Depuis un certain temps, l'humanité tente de définir collectivement sa vision du monde et de l'avenir à travers des expositions internationales. Ces expositions couvrent différents domaines : la technologie, le design, l'ethnologie, l'art et l'écologie. La plupart d'entre nous savent probablement que la tour Eiffel a été construite pour l'une des expositions universelles de Paris, et certains se souviennent peut-être même que c'était en 1889. Mais ce n'était qu'une exposition parmi tant d'autres. Les plus grandes de ces expositions, appelées expositions universelles, ont lieu plus ou moins tous les cinq ans depuis 1851. Aujourd'hui, plus de 150 pays y participent généralement et les événements durent plusieurs mois.

Entre les grandes expositions, des expositions plus petites et plus thématiques - les "expositions internationales" - ont lieu chaque année. Il convient de mentionner qu'en 2026, la Pologne accueillera l'une d'entre elles à Katowice. Dans ce bref article, j'aimerais évoquer quelques-unes des expositions les plus emblématiques et, à mon avis, les plus fascinantes, et montrer comment elles ont façonné non seulement le design, mais aussi notre mode de vie actuel. Commençons par l'ordre chronologique :

Un géant de verre et de fer - La grande exposition de Londres (1851)

Bien qu'il ne s'agisse pas vraiment de design, mais plutôt d'une démonstration musclée de la puissance industrielle des principales nations du monde de l'époque, l'exposition universelle de Londres a eu un impact énorme grâce à l'ampleur de l'entreprise. Les Britanniques ont placé la barre très haut, non seulement par les objets exposés, mais surtout par le lieu lui-même.

À l'apogée de sa domination mondiale, la Grande-Bretagne victorienne voulait impressionner le monde, et il était clair qu'elle avait besoin de quelque chose d'extraordinaire pour y parvenir. Et elle l'a fait. Le bâtiment qui abritait l'exposition, connu sous le nom de Crystal Palace, était une merveille d'ingénierie pour l'époque - et l'une des plus grandes structures de la planète. Il accueillait des milliers de pièces et des dizaines de milliers de visiteurs qui se pressaient pour le voir.

Mais le plus étonnant, c'est la façon dont il a été construit. Entièrement faite de fer et de verre, la structure modulaire a été achevée en un peu moins de neuf mois (563 mètres sur 124 et un volume de 92 000 m³). À l'époque, seules des structures comme la basilique Saint-Pierre de Rome ou le Louvre de Paris pouvaient rivaliser en termes d'échelle - et leur construction avait pris des décennies. Encore plus impressionnant, après l'exposition, l'ensemble de la structure a été déplacé de Hyde Park à Sydenham Hill, le tout en l'espace de deux ans. Malheureusement, le Crystal Palace a été détruit par un incendie en 1936, mais de nombreuses photos subsistent. Pour les personnes curieuses de connaître son histoire, nous recommandons cet article : heritagecalling.com

Cet événement londonien a fait deux choses importantes : premièrement, il a promu le concept des expositions universelles en tant que lieux où les nations peuvent se rencontrer, échanger des idées et célébrer le progrès technologique. Deuxièmement, il a lancé le rythme quinquennal des grandes expositions universelles, des événements au cours desquels le pays hôte tente toujours de présenter quelque chose de visionnaire, parfois même en définissant l'avenir lui-même.

La Tour Eiffel et la naissance de l'Art nouveau - Exposition universelle de Paris (1889)

Cette exposition a été extraordinaire non seulement parce que la Tour Eiffel a été construite à cette occasion, mais aussi parce qu'elle a été la première à présenter l'art et le design sur une aussi grande échelle, jetant ainsi les bases de l'Art nouveau.

Un grand hall d'exposition appelé Palais des Beaux-Arts et des Arts libéraux (Palais des Beaux-Arts et des Arts Libéraux) a été construit sur le Champ de Mars. À l'intérieur, les visiteurs pouvaient admirer des œuvres d'art, des meubles et des céramiques. Les amateurs de mobilier reconnaîtront deux noms importants parmi les exposants : Émile Gallé et Louis Majorelle. À l'époque, ils n'ont pas encore développé leur style, et l'Art nouveau n'émergera officiellement qu'après 1890. Néanmoins, cette exposition a contribué à éloigner le monde de la production industrielle de masse pour l'amener à apprécier à nouveau l'artisanat et les lignes fluides et organiques du nouveau mouvement.

Pour la première fois, des objets décoratifs de la vie quotidienne, tels que la verrerie, la céramique et le mobilier, ont été présentés aux côtés de beaux-arts - peintures et sculptures - leur donnant ainsi la reconnaissance qu'ils méritaient.

Source de la photo : https://www.unjourdeplusaparis.com/en/paris-reportage/1887-1889-construction-tour-eiffel-images

Quelques faits amusants : plus de 30 millions de personnes ont visité l'exposition - un chiffre stupéfiant, surtout si l'on tient compte de la portée limitée des trains à l'époque et de l'absence de voitures ou d'avions. Même les foires les plus populaires de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle n'ont pas atteint ce chiffre. Autre détail curieux : les impressionnistes n'ont pas été autorisés à exposer leurs œuvres au Palais des Beaux-Arts - ils étaient encore considérés comme trop radicaux. Pour en savoir plus sur Émile Gallé et son œuvre : La vision artistique d'Emile Gallé dans l'ameublement et Un exemple de vitrine de Gallé.

L'Art déco fait son entrée - Exposition universelle de Paris (1925)

Celle-ci n'était pas une exposition universelle dans le cycle quinquennal, mais son influence sur le design mondial - et surtout polonais - a été énorme. Officiellement nommée Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes), elle a donné naissance au terme Art Déco elle-même. Plus encore, il a essentiellement défini l'esthétique et l'orientation du design industriel pour les décennies à venir.

Cette exposition a été une vitrine éblouissante d'un nouveau style de vie marqué par l'élégance, le luxe et la richesse. L'art d'avant-garde devient l'art officiel. Le Corbusier présente son désormais iconique Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau - une maison modulaire et ouverte avec une mezzanine et une loggia. Il s'agit d'une vision audacieuse de l'architecture fonctionnelle qui a laissé une marque permanente dans l'histoire du design moderne.

L'exposition a également marqué les débuts d'un jeune étudiant danois, Arne Jacobsen. Âgé de 23 ans à l'époque, il conçoit une chaise en rotin, la Chaise Paris spécialement pour la foire. Elle lui vaut une médaille d'argent. Dans les décennies qui suivirent, Jacobsen devint l'un des designers danois les plus célèbres, et ses meubles se vendent encore aujourd'hui par millions.

Pour la Pologne, il s'agissait d'un événement marquant. C'était la première fois qu'elle avait l'occasion de se présenter sur la scène internationale après avoir recouvré son indépendance. Le pavillon polonais a attiré l'attention et de nombreux artistes polonais ont reçu des médailles et des prix. Jan Szczepkowski a remporté le Grand Prix pour une crèche de Noël. Zygmunt Kamiński a reçu des distinctions pour ses dessins des nouveaux billets de banque polonais. Zofia Stryjeńska a obtenu pas moins de quatre Grands Prix, une distinction spéciale et la Légion d'honneur. Cette exposition a donné le coup d'envoi de l'ère Art déco polonaise, qui est devenue le style officiel de la deuxième République polonaise jusqu'à l'éclatement de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. https://www.whitemad.pl/miedzynarodowa-wystawa-sztuki-dekoracyjnej-w-paryzu-1925-polskie-wzornictwo/

Source de la photo : Wikimedia Commons (domaine public)

La ville du futur - Exposition universelle de New York (1939)

Intitulé Le monde de demain, Cette foire a eu une influence profonde sur la façon dont les gens - en particulier les Américains - imaginaient l'avenir. Sa pièce maîtresse était Futurama, L'exposition est une vaste maquette en mouvement d'une ville futuriste, conçue par Norman Bel Geddes pour General Motors.

Cette vision a ensuite façonné le développement urbain américain pendant des décennies : banlieues tentaculaires, autoroutes et essor de la voiture particulière. Sans surprise, les constructeurs automobiles ont soutenu et promu cet avenir, qui correspondait parfaitement à leurs intérêts commerciaux.

Mais ce n'est pas tout. C'était aussi la première fois que le public assistait à des démonstrations en direct de technologies émergentes qui allaient changer le monde : la télévision, le four à micro-ondes et un premier prototype d'ordinateur. En bref, la foire offrait un aperçu de l'avenir même dans lequel nous vivons aujourd'hui.

Le monde transformé par la technologie - Expo d'Osaka (1970)

Il s'agit de la première grande exposition universelle organisée en Asie, et le Japon saisit l'occasion pour présenter sa vision de l'avenir. Le pays avait déjà étonné le monde avec des infrastructures de pointe lors des Jeux olympiques de Tokyo en 1964, où le train à grande vitesse (Shinkansen) avait fait ses débuts, atteignant plus de 200 km/h. Mais l'Expo d'Osaka proposait quelque chose d'encore plus futuriste : le train à sustentation magnétique, ou Maglev. Mais l'Expo d'Osaka propose quelque chose d'encore plus futuriste : le train à sustentation magnétique, ou Maglev. Il flotte au-dessus de la voie ferrée et atteint une vitesse de plus de 500 km/h. Le train est même apparu sur les affiches officielles de l'Expo.

Cette exposition a symboliquement marqué le début de la domination mondiale du Japon dans le domaine de la technologie. En l'espace de quelques décennies, des villes comme Osaka et Tokyo allaient devenir quelques-uns des plus grands centres urbains du monde. L'exposition a présenté un certain nombre d'innovations visionnaires :

Première présentation publique de prototypes de téléphones mobiles (NTT)

Premières démonstrations de réseaux informatiques - les prémices de l'Internet

Véhicules électriques et trains à grande vitesse

Les premiers robots humanoïdes

L'une des plus grandes attractions était un orchestre robotisé appelé Symphonitoron. Écoutez-les jouer : Lien YouTube, Photos de l'Expo : archdaily.com.

En 2025, l'Expo revient à Osaka. L'événement s'intitule Concevoir la société de demain pour nos vies.

Qu'y verrons-nous ? Comment imaginons-nous l'avenir, 55 ans après la précédente Expo au Japon ? Quelles visions les différents pays présenteront-ils ?

J'espère pouvoir vous le montrer en personne - et essayer de répondre à vos questions en cours de route.

Rendez-vous à Osaka !

Adam Krzemiński – PDG

Adam Krzemiński est diplômé en droit, mais sa passion pour l'archéologie l'a conduit à la découverte et à la restauration de meubles, qu'il considère comme des objets historiques. Il a commencé par restaurer des antiquités en Europe et aux États-Unis, mais s'est rapidement intéressé aux pièces du XXe siècle. En 2014, il a fondé Futureantiques, une entreprise spécialisée dans le mobilier et l'éclairage modernes du milieu du siècle. À ce jour, les articles de la collection Futureantiques ont trouvé de nouveaux foyers chez des clients dans plus de 27 pays, 400 villes et sur quatre continents.

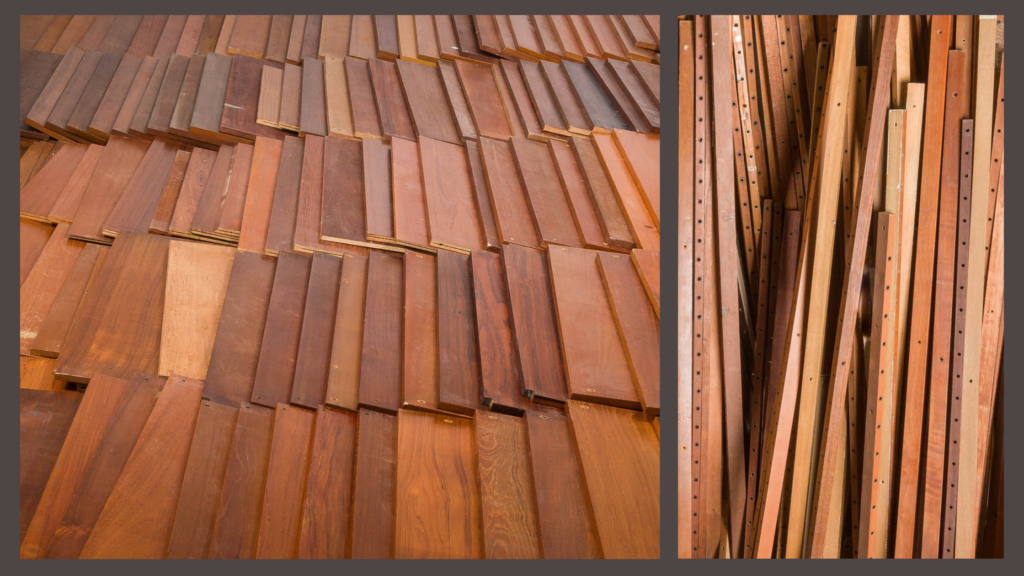

Meuble mural Ergo à une travée en teck, par John Texmon, Norvège, années 1960

Meuble mural Ergo à une travée en teck, par John Texmon, Norvège, années 1960